This article is part of an installment of essays and examples illuminating the essence of good architecture, which, as Slow Space founder Mette Aamodt defines, comprises the three fundamental qualities of empathy, experience and beauty. The exploration of Peter Zumthor’s thermal baths in Vals, Switzerland, represents a paragon of architecture as experience — as an extraordinary sensory experience.

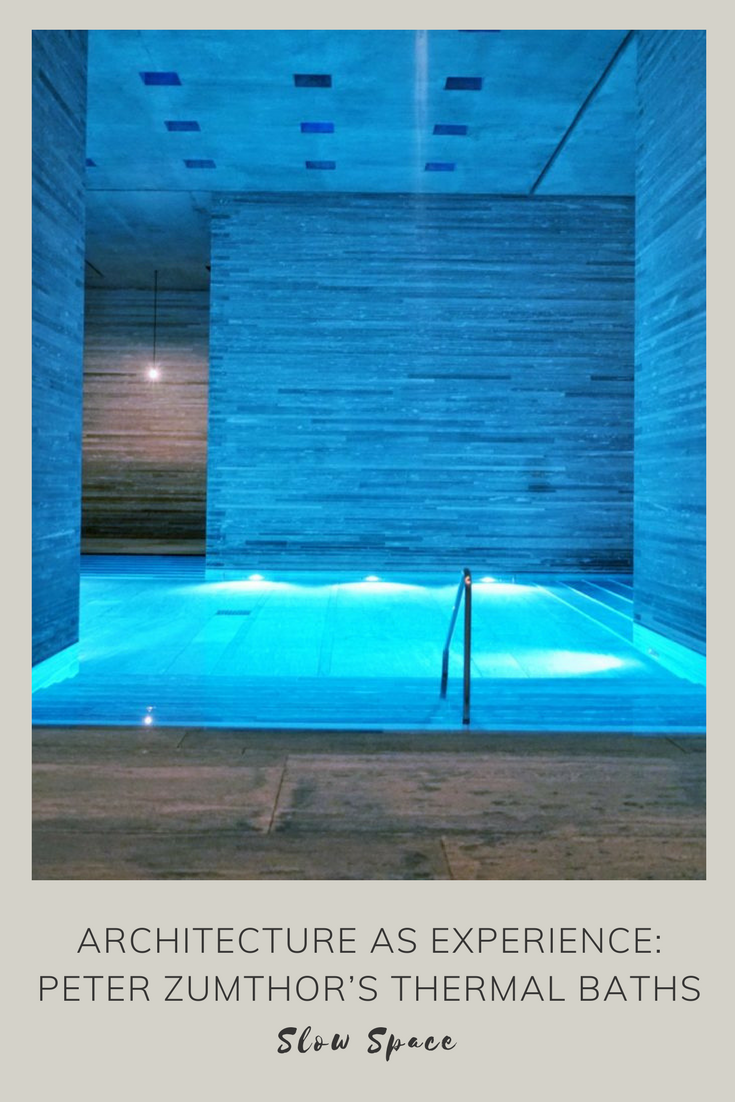

Photo by Jonathan Ducrest

Solitude of space

To share a taste of this experience, we caught up with Swiss photographer Jonathan Ducrest, who explored Peter Zumthor’s thermal baths from a distinctive angle — from behind his sly camera lens — shot without special lighting. Ducrest, who says he’s “not big on taking pictures of people,” also minimally edited the photographs to give a more authentic sense of the place’s raw simplicity. It is the solitude of space that fascinates the photographer.

Ducrest now calls Los Angeles home. He’d returned home to his native Switzerland for the holidays and decided to take his mother on a spa weekend. “This was my third or forth trip to Vals,” says Ducrest, contemplating how time moves slower in the small mountain village of fewer than one thousand souls in Switzerland’s Graubünden canton. “You just relax, without the everyday stress. You can walk and enjoy nature, and there aren’t a lot of distractions.”

View into the surrounding landscape of the valley of Vals. Photo by Jonathan Ducrest

Swiss minimalism

Zumthor, whose other significant works include the Kunsthaus in Bregenz, Austria, the all-timber Swiss Pavilion for Expo 2000 in Hannover, Germany, and the upcoming expansion of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in the United States, designed the spa building over the canton’s only thermal springs. The hydrotherapy center, commissioned by the village of Vals, was completed in 1996. Zumthor’s rectilinear design contrasts the valley’s traditional vernacular structures and pastoral setting, and was to look as if it pre-dated the luxury hotel complex.

Zumthor’s minimalist, clean-lined design contrasts the valley’s traditional vernacular structures. Photo by Jonathan Ducrest

“The spa and the hotel itself — it’s like this temple,” reflects Ducrest. “There’s nothing but the water and the stone the architect used.” The cave-like structure comprises 15 units, each five meters high, whose grass-covered concrete roofs don’t join. The slim gaps are filled in with glass. The dark quartzite slabs are quarried locally, and 60,000 one-meter-long stone sections clad the walls in a subtly ordered pattern. “He framed the landscape outside with windows,” the photographer describes. “It’s like you’re watching a painting when you’re relaxing in your chair, and you’re looking out and it’s snowing or the light is changing or there could be a storm outside. You’re becoming more attuned to your surroundings.” The fact that all the stone Zumthor used was brought in from the valley connects visitors even more to the encompassing environment. “Everything comes from there: the waters, the air, the sounds.”

Everything comes from there: the waters, the air, the sounds.

Photo by Jonathan Ducrest

Ducrest has long wanted to photograph the space. But without an official assignment, he needed to be cunning in shooting inside the thermal baths, beginning his day’s work early in the morning, when only hotel guests are allowed in. Having been in the space before, he knew beforehand what he wanted to capture. “I had my camera wrapped in my towel, and my mom was looking out if someone was coming. And I took the pictures in a natural light, there’s no flash,” reveals Ducrest, who intently refrained from retouching the photographs. He wanted to depict the architecture as purely as possible — in the way it was designed. What is more, he says, “The lighting changes throughout the day. If you start incorporating lighting that’s not supposed to be there, it’s going to change the feel of it. I like the fact that I had to deal with those constraints. And I don’t really like having people in my photography.”

I don’t really like having people in my photography.

Photo by Jonathan Ducrest

Photo by Jonathan Ducrest

Feeling Zumthor

By design, Zumthor, who received the Pritzker Architecture Prize for his lifework in 2009, pulls the visitor from the arrival and physical transition into bath attire deeper into the spacial experience of the building. A gentle slope leads down to the locker rooms. “You go down this dark tunnel, and you get glimpses of what he wants you to go and explore,” the photographer tells. “As you walk down the hallway, you turn to your left, and there’s this small but very tall opening, and you can see the space below. You see a pool, and you want to go there and see that space. You’re going through a turnstile, and again, you walk this hallway, and there’s water coming out of little water sprouts.” At the end of the hall, the locker rooms lie behind heavy curtains. “You emerge on the other side into the main space, and as you are walking down the staircase, you’re going to see the outdoor pool. You’re going to see a part of the main pool. And you’ll again want to go further and explore.”

Rigid and in order: Swiss minimalism. Photo by Jonathan Ducrest

Ducrest’s images are a pictorial reflection on the architect’s intent of creating a physical, mental and spiritual human experience — with the Swiss touch of the internationally renown architect, who was born in Basel in 1943, the son of a master carpenter. “In Switzerland, we like things in order and a little rigid, that’s how we are. That’s still how I am,” Ducrest notes. “When you’re there, it’s always straight lines. It’s hard corners. From the design, you wouldn’t think there is something soft or calming about the space. It’s very rigid and square, and there seems to be no end to this gray stone. But then you add the thermal water elements and the lighting, and it all comes together. Now, it’s a perfect space.”

The soft element of the thermal water in juxtaposition with the rough stone and the straight-line architecture perfects the experience of the space.

Also read: “Designing With Empathy” by Mette Aamodt