The Slow Space Movement stands for buildings that are good, clean and fair, but what exactly do we mean by that? This is our inaugural piece in a series of articles exploring this thematic trifecta of what we understand slow space to be, beginning with “good.”

In our practice at Aamodt / Plumb, we define a good building as a building that holds meaning for the users, brings them joy and connects them to the world, to others or to themselves in some way. A good building does not just satisfy our basic needs but helps us to understand ourselves and our place in the world. It mediates between our being and our environment, providing a filter through which we can see ourselves and the world. It is not a benign shelter, but a lense that we create for experiencing the world and ourselves within it.

As architects, designing a good building is a hard, if not impossible, task, but one that we choose to strive for every day. One of the ways we can pursue good building is through empathy.

Feeling what they feel

Architecture and Empathy, 2015. Published by The Tapio Wirkkala-Rut Bryk Foundation.

Empathy is putting yourself in someone else’s shoes and feeling the emotions they feel. According to Juhani Pallasmaa, empathy in architecture is when “The designer places him/herself in the role of the future dweller and tests the validity of the ideas through this imaginative exchange of roles and personalities.” (Pallasmaa, Juhani. “Empathic and Embodied Imagination: Intuiting Experience and Life in Architecture” in Architecture and Empathy.)

Empathy is one of our basic human traits and one that differentiates us from other species. It evolved to nurture babies outside of the womb, as our upright position forced babies to be born before full gestation. Babies continue to develop through skin to skin contact with their mothers. Without this babies fail to thrive and suffer irreparable physical and psychological damage, and sometimes death. Architect and philosopher Sarah Robinson has argued that the skin is the most fundamental medium of contact with our world.

“Boundaries of skin: John Dewey, Didier Anzieu and Architectural Possibility” in Architecture and Empathy

“Empathy allows us to connect to the world through our own bodies and in turn, the world opens itself up to us as we feel our way into it. As the mutuality of the mother-baby relationship exemplifies, we dwell in a reciprocating circuit. We are built to be received into a world to which we must connect, into a world that fits us. Empathy is the deep reflexivity at the heart of life.” (Robinson, Sarah. “Boundaries of Skin: John Dewey, Didier Anzieu and Architectural Possibility” in Architecture and Empathy.)

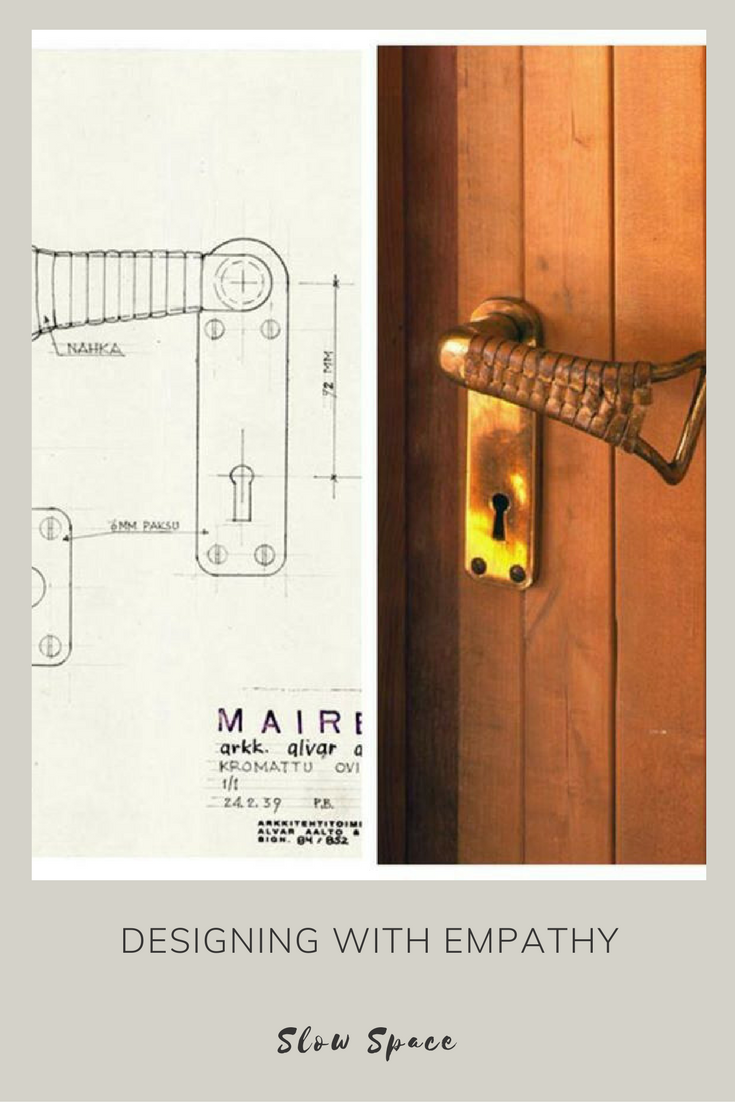

The leather-clad door handles at the Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto are an example of how sensitive the architect was in designing the physical point of connection between the user and the building. Instead of leaving the cold metal bare to draw heat away from the body, he wrapped them in leather so the contact would be skin to skin.

Embodied simulation

Recent discoveries in neuroscience have identified exactly how empathy works within our bodies. Mirror neurons in the brain create a mechanism, called embodied simulation, that maps the actions, emotions and sensations of other people onto our brains as if we were experiencing them ourselves. Embodied simulation is not just limited to empathizing with people, it extends to objects and space. MD PhD Vittorio Gallese, who along with his team discovered these mirror neurons, says that “Embodied simulation not only connects us to others, it connects us to our world — a world inhabited by natural and manmade objects … as well as other individuals.” (Gallese, Vittorio. “Architectural Space from Within: The Body, Space and the Brain” in Architecture and Empathy)

“The notion of empathy recently explored by cognitive neuroscience can reframe the problem of how works of art and architecture are experienced, revitalizing and eventually empirically validating old intuitions about the relationship between body, empathy and aesthetic experience.” (Ibid.)

Human-centered design

Empathy is a cornerstone of human-centered design, a buzzword that has been nicely packaged and branded by IDEO, the interdisciplinary design consulting firm.

“Human-centered design is a creative approach to problem solving and the backbone of our work at IDEO.org. It’s a process that starts with the people you’re designing for and ends with new solutions that are tailor made to suit their needs. Human-centered design is all about building a deep empathy with the people you’re designing for; generating tons of ideas; building a bunch of prototypes; sharing what you’ve made with the people you’re designing for; and eventually putting your innovative new solution out in the world.” (IDEO Design Kit)

This description is how I always understood architecture, but I am grateful to IDEO for spreading these ideas to the mass market. But why does human-centered design seem so out of fashion inside our industry? What is it in contrast to? It is in contrast to market-driven design, like developers who are often just concerned with maximizing square footage and reducing costs. We are all pretty familiar with these examples.

Technology-driven design

Then there is technology-driven design that I will call “tech for tech’s sake.” Quoting a recent opinion piece in The Guardian, “If there’s one thing the technology community loves, it’s an over-engineered solution to a problem that isn’t really a problem. Double points if the root of that problem is: ‘I’m a young man with too much money who needs technology to do for me what my mother no longer will.’ ” (“The five most pointless tech solutions to non-problems,” The Guardian) At the top of their list of the most useless tech solutions is the Juicero, a $400, Wi-Fi-enabled machine that squeezes single-purpose pods filled with crushed fruit and vegetables into a glass. This company raised $120 million in venture capital. PS: It turns out, if you just squeeze the pod, the juice will come out ready to drink. No machine needed. (Juicero has suspending the sale of the Juicero Press and Produce Packs in September 2017.)

Tech as tech can: Render of Zaha Hadid’s design for the headquarters of the Central Bank of Iraq. Photo: Zaha Hadid Architects

Technology-driven design has dominated architecture for the past 20 years, where the cutting edge has been defined by what wild architectural form could be created by the latest software and material technology. The work of FOA, Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry comes to mind. The green movement has also been swept up in technology-driven design, with everyone searching for the tech equivalent of the silver bullet that will solve our environmental crisis.

“True sustainability demands more than technological solutions — it must be founded on an understanding of human nature that recognizes, affirms and supports our nascent vulnerability and interdependence.” (Robinson, Sarah. “Boundaries of Skin: John Dewey, Didier Anzieu and Architectural Possibility” in Architecture and Empathy.)